Family History

Category: History

About This Course

This course aims to provide a broad understanding of genealogy and how to go about discovering your family history. The originating course was written by Scott Taylor (Glasgow & District Amal Branch) and Craig Finnie (WEA & Scottish Union Learning). This online version has been developed with the help of Denise Hennigan (Eastern No 6 Branch) and Paul Dovey (CWU Equality, Education & Development). Each of us have been conducting research into our own families for many years.

With TV programmes like Who Do You Think You Are? and the proliferation of online genealogy sites, complete with archives of historical records, there are more people looking into their family history than ever before. But whether you conduct your research online or on the ground you will need much the same skills.

By the end of this course you will have learnt;

- How to understand and populate a family tree

- How to plan your research

- How to use a questionnaire for gathering information from relatives

- How to interpret old writing and language

- How to extract information from birth, marriage and death certificates

- What the census is and the information it contains

- Other records that might be useful

- To look out for events you might not have expected

- How to put your research into historical context

- What DNA can and can’t tell us

- About the different online tools that are available

- Tips and tricks for when things go wrong

- Options for presenting your findings

Family History Is For Everyone

Researching your family history used to be something that only the wealthy or those with plenty of time could engage with. Now, thanks to so much information being readily available, anyone can do it.

All Families Are Different – And They Always Have Been

Although we think of our families as personal to us, they are also social units, upon whom politicians, religious and community leaders have often sought to make judgements about what is “normal” or “acceptable,” often reflecting the power imbalances of class, ethnicity, gender or sexuality. This meant that people had to think about what information they provided on official documents, but as we learn to read between the lines, genealogical research will show our ancestors experiencing all of the same difficulties we experience now. Extended families were common, with many generations of uncles, aunts and cousins living nearby and supporting each other. Step-families were common, as were adoptions and other long-term childcare arrangements. Without the support of these extended relationships people were forced to rely on the limited and judgemental support of the poor law and the workhouse.

Resources

- Gender roles in the 19th century: A blog from the British Library exploring attitudes towards gender in 19th-century Britain.

- Foundlings, Orphans And Unmarried Mothers: This British Library blog by Ruth Richardson explores the world of poverty, high mortality, prejudice and charity that influenced the creation of Oliver Twist.

- LGBTQ Genealogy: A blog by Stewart Blandón Traiman recognising the inevitability of LGBTQ ancestors and how we might recognise and acknowledge their lives.

- How To Look For Records Of Sexuality And Gender Identity History: A research guide from the National Archives. Sadly, we have to acknowledge that many official records will relate to the criminalisation and persecution of LGBTQ lives.

What If My Ancestors Came From Abroad?

Migration has always played a part in human history and our family histories are no different. Historical records show a series of migrations over time, with movement both in and out of the country. There are numerous websites and resources that help us to identify those of our ancestors who came from abroad. Most genealogy sites offer access to international information and resources. Many community-specific websites and organisations can offer advice and resources to help us with this task.

Resources

- The Best Websites For Tracing Caribbean Ancestors; A blog from Who Do You Think You Are, reviewing some useful websites for those tracing their Caribbean ancestry.

- JewishGen; A free site specifically designed to help people of Jewish heritage trace their ancestry.

- Irish Genealogy; An Irish Government archive of births, marriages, deaths, census records and legal documents.

- Ancestors From The Indian Subcontinent; The guide from the Norfolk Records Office lists resources that may help you discover more about your ancestors from South Asia.

Genealogy & You

What Is Genealogy?

Genealogy is the line of descent of a person, family, group, etc. It is the study of a family’s ancestry and history. It traces a lineage back in time, from you to your parents, your grandparents, great-grandparents and so on. Quite quickly you begin to build up a history of where you came from and the history of your family.

Figure 1 shows a famous family tree. At the top is the grandparents. The middle is the parents and at the bottom are the kids.

So What Does This Mean For Me?

It depends on what you’re looking for. And that will depend on your particular family circumstances. The first thing to remember is that all families are different. If we focus solely on going back as far and fast as we can, then we might miss a lot of fascinating details of how our families actually lived. Our families will include step family, adopted family, extended family and all sorts of other people who might have been a really important part of our family story but might not be recorded in the places we might immediately expect to find them. That’s before we even start looking at the communities and the times in which they lived. In this course we will look at a range of documents that help us to get a better idea of how our ancestors lived.

Why Do We Do It?

For some people creating their family history is just a personal project. Others want to show it to their family when they have finished. For others their motivation might be to solve a family mystery or missing link. Others look at it as a social history project to get a better understanding of how their family came to be what it is today.

Activity 1: What Are Your Reasons?

Take a moment to think about your reasons for doing this course. Jot them down on a piece of paper. Thinking about what you want to get out of it will help you to plan your research later.

Family Trees

What is a family tree?

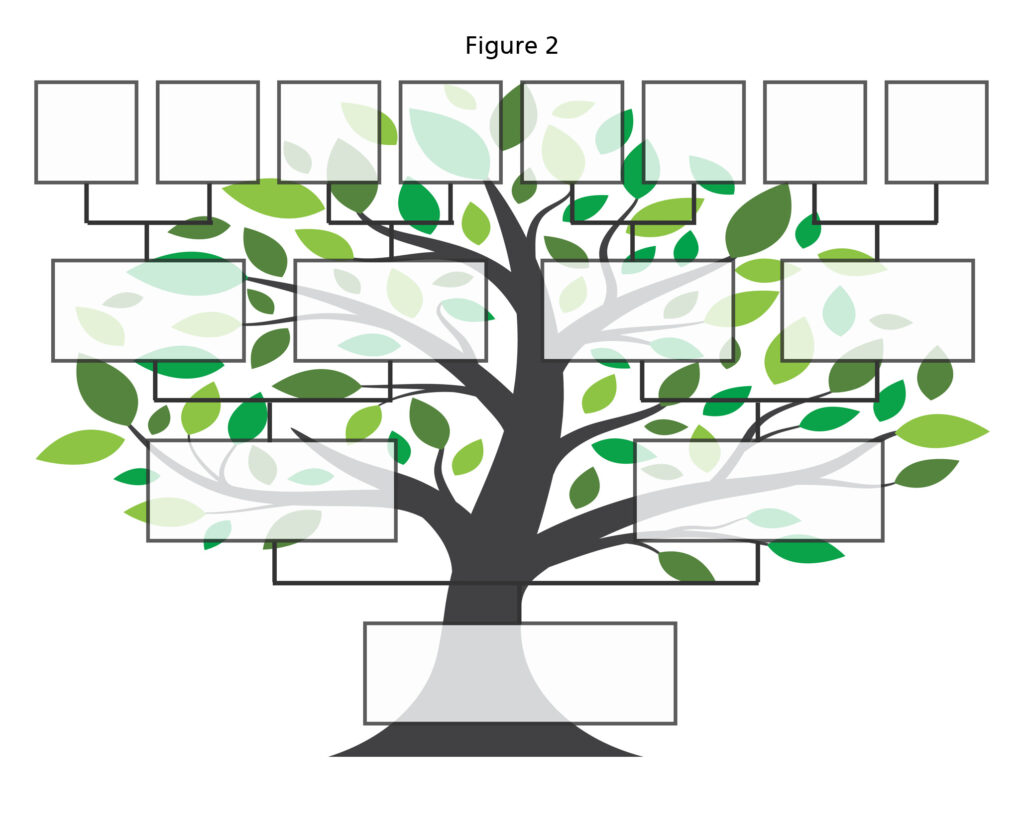

A family tree is a chart showing ancestry. Because for every parent, there will be two more parents this creates a branch. This collection of branches makes a tree. Each level up the tree represents another generation. Your name goes on the box on the lowest level. Your parents go on the next level up. By convention the male or paternal line goes to the left. The next level up are your grandparents. Then your great grandparents etc. etc.

There are many different types of charts. There is no right or wrong. The chart you choose will depend on which displays your information most clearly. Figure 2 shows a decorative family tree where you can add pictures or names.

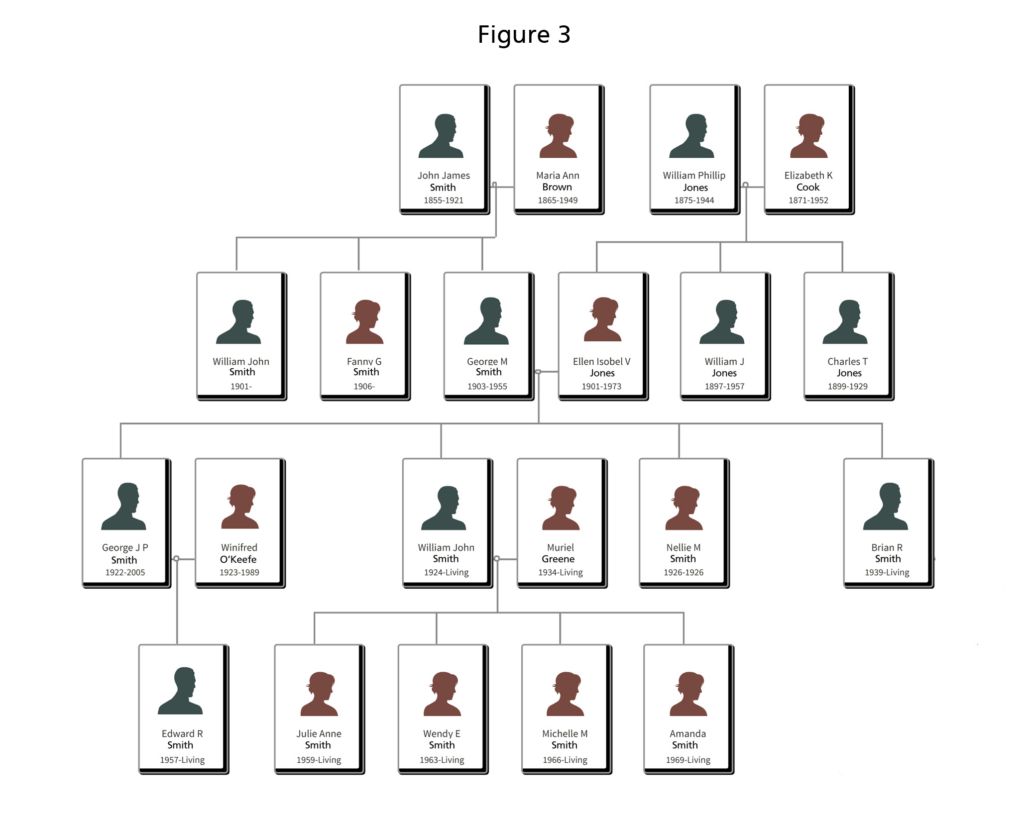

Do you notice anything about the tree in Figure 2? The is no room to add brothers or sisters (siblings). This is a form of Pedigree Tree that enables you to show family lineage more clearly by focusing solely on parental relationships. The type of family tree you are probably most used to seeing is a descendant chart as in Figure 3. This follows the same principle of one level for each generation – but it allows space for siblings and cousins etc. This can be important if you want to get a better understanding of your family history – or to check that you have got the right ancestor rather than someone else with the same name!

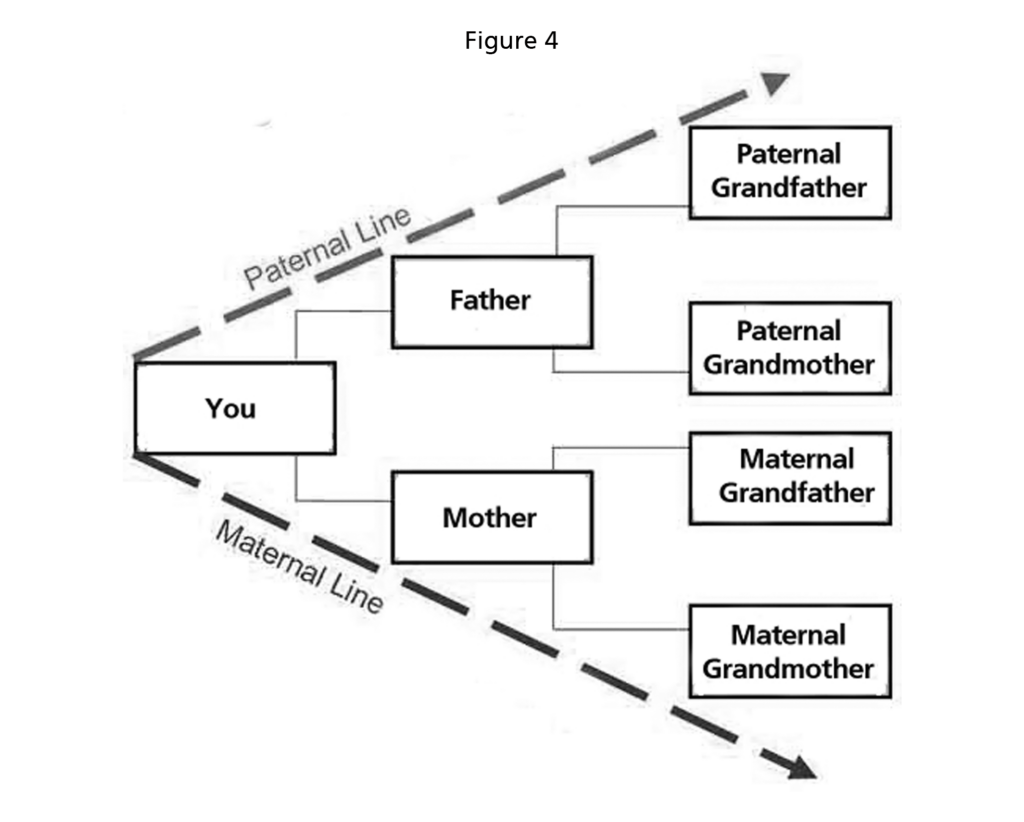

You will often see pedigree charts laid out from left to right – such as in Figure 4. This works on the same principle of a level for each generation but this time from left to right. Once again this is a direct ancestral lineage with siblings excluded for the sake of clarity.

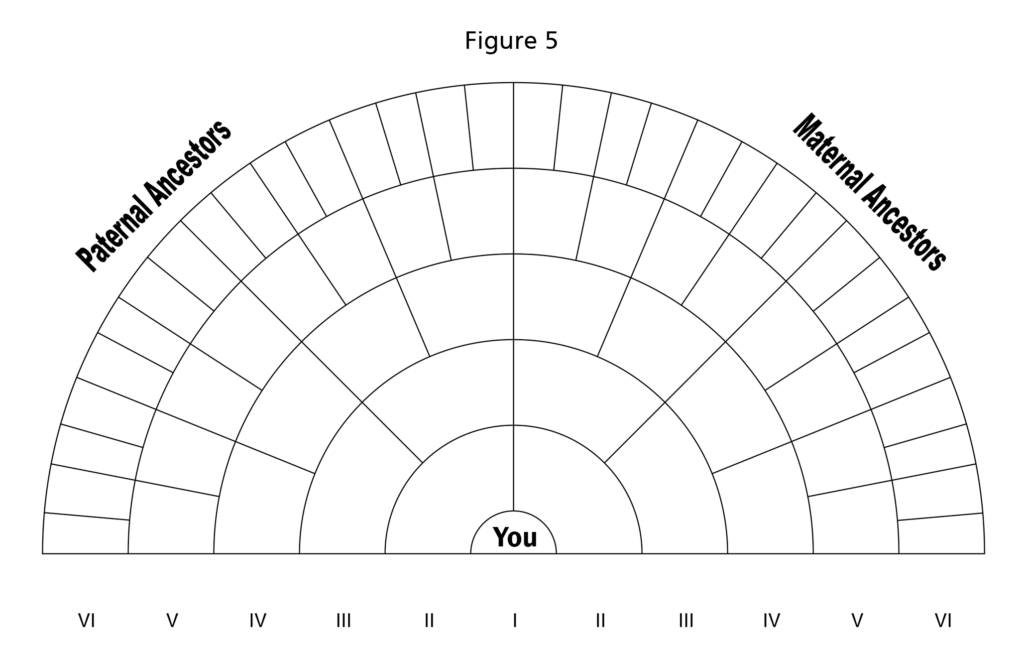

Another popular form of pedigree chart is the Fan Chart. This is a circular or semi-circular chart with you in the middle and you ancestors radiating out from you, as in Figure 5.

Activity 2: The Family Tree

Click and drag the relatives into the right place in their family tree. There might be a few gaps but all the relatives can only go in one place from the information you are given.

“Hi, my name is Jack. I have a brother and sister called David and Sharon. My mum and dad’s names are Mark and Sophia Stewart. My grandfather MacDonald married Helen Gates while he was serving in the army. My other grandparents are Jessie and James.”

“Hello, my name is James. I am Jack’s grandfather and my dad shared the same name as my grandson. My mother died in childbirth and I never knew her.”

“Hello, my name is Helen. Whenever my granddaughter Sharon comes to visit we always talk about our family history. She loved to hear stories of my mother and father, Elizabeth and John.”

Resources

There is wealth of different genealogy charts available to freely download online. Here are a couple of useful links. We suggest you bookmark these for later.

- Free Family Tree Templates https://freefamilytreetemplates.com/

- Family Tree Templates https://www.familytreetemplates.net/

Starting Your Research

You Are Unique!

Look at Figure 6.

- Find George M Smith on the second from top row. Although he shares his ancestry with his siblings, if he gets married he links to the Jones family tree. Their children will have the ancestry of both Smith and Jones.

- Through their own marriages, their children will have the ancestry of Smith and Jones – and that of O’Keefe or Greene. All their subsequent generations will incorporate the ancestry of another parental line.

- This means that, despite being part of something incredibly huge, you are also unique! No-one else’s perspective will be quite the same as yours – and neither will their research.

- But equally, your research could feed into that of many different people who you did not even know existed. Websites mean that mistakes can spread rapidly, so we all owe it to each other to ensure our research is accurate as it can possibly be.

Getting Organised

Sometimes people find the idea of doing research daunting, but all it takes is a bit of organisation and planning. Having a research plan will develop your skills of reasoning and understanding while building a family tree and writing a story about your history.

Information & Storage

At its most basic all you need to do research in a source of information and somewhere to store it. Click on the headings to see more.

Keep It In Order

Once you get started, you will be surprised how quickly your collection of genealogical records grows. If you don’t keep it in order it could quickly get out of hand. Whether you are using paper or computer files you will need to create a filing system. Think about a file for each branch of your family, with subfolders for each individual within it. Don’t forget that over the generations names are likely to repeat, so including a Date of Birth in the file name will help to keep things clear. In each individuals’ file you can keep all the relevant documents, certificates, photos, maps or anything else that helps to explain how your ancestors lived. The nature of genealogical research means that there will be lots of cross-referencing. Keep a separate ancestor record for each individual on which you can record all their relevant life events. Using the appropriate family tree charts will help you to visualise the relationships.

Keep It Secure

Remember to store your information securely. Keep a back-up copy of whatever you save and don’t rely on websites to store your information, they might crash, go bust, or change their terms of service, leaving you without the information you have worked so hard to collect. Most websites allow you to download a GEDCOM file of your tree, which is a standard format compatible with most genealogical websites and software. It is worth getting into the habit of regularly downloading a copy of your data as a back-up.

Write It Down

Writing things down helps you to develop a plan to tackle your family history and break it into manageable chunks. The key document will be the ancestor record that you write for every individual. This will hold all their key life events. It is worth writing down as many details as you can gather. There are a range of downloadable templates for this – but the template should inform rather than dictate the information you collect. Sometimes it is the most obscure information that provides the clue to go back another generation. So, if you find a really interesting piece of information about an ancestor, make a space to record it even if it means amending your template for this entry. If you don’t write it down you might forget it or become confused as to which ancestor it relates to. Once your family tree begins to grow, this is very easily done.

Writing the information down also helps you to identify your next steps;

- Are there relatives you can talk to?

- Are you tracing the fathers’ (patrilineal) line, the mother’s (matrilineal) line – or both?

- How far do you research into offspring and siblings?

- Do you know where they lived?

- What documents do you have?

- What is available online?

- What is available in museums, libraries or parish records?

- Can we contact them or do we need to plan actual visits to these places?

As we saw earlier, everyone’s family is different, so what you choose to do will depend on your circumstances.

Primary & Secondary Sources

Sources of information are often categorized as primary or secondary depending upon their distance from the event. The following short videos from the Open University explain this. Click on each video in turn to play. Close each video once it has completed in order to move on. Captions can be enabled within each video.

While researching your family tree you will become very familiar with a range of primary resources. But don’t forget the secondary resources. They can save you going through reams of original documents. They can guide you and provide good examples of research strategies, and they can help you position your search within the wider study of the subject. Click on the image below for more examples.

Research Skills

Research is all about finding the answer to a question or a solution to a problem. So your first job is to define the question. The initial question might be quite broad, such as who was my great grandfather? But as you look deeper into their lives your questions will become more detailed: When and where was he born? Where did he live? What was his job? What was the neighbourhood like? What did this job entail? And so on.

To find the answers to these questions you will need to gather information relevant to the question. You will notice that some of the questions above are specific to my great grandfather; such as when and where he lived. Others are more general, such as information about the local area or descriptions of what a certain job entailed. You will find the answers to the personal questions in records such as birth and marriage certificates or census forms. But information about neighbourhoods or types of employment are more likely to be found in history books, reports, journals or museums. Part of your research process is discovering where to look for the answers.

Another important aspect of research is the ability to review and analyse the evidence. Standards of evidence are very important because not all evidence is of the same quality. Primary sources are generally taken to be fairly reliable sources as they will be personal recollections, official documents or reports from the time – but even these will not be wholly free of bias. Personal recollections may be tainted by the passage of time or the wish to hide embarrassment. Official documents are shaped by the biases and assumptions of the time and whoever is collecting the data. Reports may be shaped by the authors point of view, who commissioned them or how the evidence was selected.

These days, many local and amateur historians have websites and blogs that can be readily accessed online. Some can be excellent sources of specialised information – but others can be less reliable; repeating hearsay and dubious claims. A reputable historian should reference their sources so that the reader can check their validity or look into them in more detail. If someone does not reference their sources, or only uses a select few, then this might be a sign that their research is not as rigorous as it could be. Do not just take references at face value. If a reference is particularly important to your argument, check it out to see that the evidence has been taken in context.

Articles in peer reviewed journals are good sources of information because their arguments have been tested by other historians but even here you will sometimes find contesting views. In such situations you need to read around the subject and appraise yourself of the different positions. You might end up being convinced by one side or the other or you might equally legitimately conclude that it is a contested area that needs more evidence for you to come to a definitive conclusion. Maintaining high standards of evidence is to treat our ancestors with the same respect afforded to kings, queens and politicians. It means finding as much supporting evidence as we can until we are confident that, on the balance of probability we have proven our theory to be correct. This really matters because many web-based genealogy sites will use the links you create to guide others. If you accept something on face-value it can find its way into the system and mislead others.

One thing all researchers need is plenty of patience. Sometimes the information almost falls into your lap, but at other times it can be hard to find, lead you up many false paths and twists and turns. You have to treat your genealogy as a puzzle and not be put off by these set-backs. We all have them. The most important thing is to thoroughly test your information.

- Does it stand up to scrutiny?

- Is it really related to the person in question?

- Check other relevant documents for information that either supports or contradicts your theories.

- Make this an ongoing process that you will review as you gather more information.

Look at Figure 7 to see how this works. Click on the i signs to see more.

As you research you will keep going through these cycles, constantly improving your knowledge, testing what you think you know and making your research ever more reliable.

Activity 3: Starting Your Research

Have another look at the charts and information sheets listed below. Use them or something similar of your own to make a start on your research. Start small; choose one branch of your family tree and just one or two generations. Start filling in what you already know and identifying where the gaps are.

Resources

- Free Family Tree Templates https://freefamilytreetemplates.com/

- Family Tree Templates https://www.familytreetemplates.net/

- CWU Family History Handout: Historical Sources & Research Skills

- Harvard Guide to Using Sources: Evaluating Sources

Get Talking

The Treasure Trove On Your Doorstep

As we have already seen, the first place to start building your family tree is at home. Other family members will have information that you don’t. Older relatives might have memories and stories of relatives who are now deceased which can give a depth of character that you cannot get from documents alone. They can also give you clues to new places to search for information.

Using A Questionnaire

If you are asking your relatives for information it is worth preparing a questionnaire. You do not necessarily need to go through it line by line but it provides a handy checklist to ensure you’ve covered everything you wanted to discuss. The person you are talking to will probably get side-tracked into different family anecdotes and tales but you should embrace this as they might reveal facts that you were completely unaware of.

But please remember, these stories from the past could range from the very happy to sad and traumatic. Be tactful and respect the feelings of those you are interviewing. Digging into the past might also reveal old family feuds or disputes. Once again, use tact to avoid opening old wounds.

When preparing a questionnaire you need to ask yourself what you want to know and what questions will draw this information out. Use open rather than closed questions; you will learn more. Make notes as you go or, if it doesn’t put your interviewee off, consider recording your session.

Types Of Question

The type of question you ask will influence how much information you get from the reply. Think about whether your question is Open, Closed or Leading. Click on the i sign to find out more.

Questions To Ask

The questions below will provide useful information whether we are thinking about interviewing a living relative or searching for information on a deceased relative. It is not an exhaustive list. A quick online search will generate hundreds more suggestions but a particularly good place to start is the History Begins At Home website, which has lots of questionnaires, tips and tricks to get you started. Everyone will be different so you might need to ask supplementary questions to reflect this. Remember to leave time for open questions and give your relatives space to talk.

- What is your name? It may be obvious but do you know if they had a middle name or not.

- What is your date of birth? These days most people know this – but in the past it was common to only have a rough idea.

- What is your profession? Knowing what kind of job someone has can help find more about them.

- Where did you live? Knowing where people lived helps you to identify them from others.

- How many brothers or sisters do you have? This can be used to build up a family tree and makes it easier to identify the correct household.

- When did you get married and where did you first meet? This will help you to develop a picture of the family, providing information on parents and identifying the matrilineal line going back.

- Do you know when and where your mother and father got married? Knowing date and place of marriage will help you track down documents and provide further information on parents and grandparents.

- Do you know when and where your father or mother was born? Knowing date and place of birth can help you to find previous generations and further documents.

- Do you remember what schools you went to? This will help to locate the person in their community and help generate a timeline for this person.

Activity 4: Interview Questions

Click on the link to History Begins At Home website and looks at the sample questionnaires they have there. Use them to broaden your thinking on your own family history. Are there any other helpful questions you can think of to add? Think about friends or relatives you might be able to interview to find out more about your family history or the history of your community.

Resources

- History Begins At Home https://www.historybeginsathome.org/

Handwriting & Literacy

All family historians come across the problem of deciphering difficult handwriting at some stage. It may arise from a number of causes, not only the poor skill of the original writer. Documents stain and deteriorate easily, sometimes becoming extremely creased, sometimes having their top surface eroded, leaving only partial traces of what was originally written. There are, however, some things you can do that will help you decipher them.

Whenever you encounter an unreadable word, you should seek out another part of the text that is more legible. Most writers form their letters in a consistent manner, so you need to learn the handwriting quirks of the writer in question. Also, many documents use stock phrases and a consistent format, which may provide further clues. So pressing ahead fairly quickly on your first attempt may be helpful, even if you then have to go back to fill in the earlier details. Be prepared to re-read the document several times as you fill in the blanks

There is also the problem that many people were unable to read or write so someone else had to fill paperwork in for them. This might introduce errors or misunderstandings – for example writing Hester as Esther might have you looking for a sister who doesn’t exist. Check as many documents as you can. Check for dates and places of birth. Look at documents that record multiple family members. As you collect more documents, you will have a better chance of identifying errors in the original documents.

Nowadays there is also the problem of transcription for online archives. This is done in bulk and often by people unfamiliar with the local area, so mistakes inevitably occur, for example writing Devon in Kent rather than Dover in Kent. You might be able to infer this transcription error from the county, but if there was no county recorded then it could be really confusing. Always look at a copy of the original document if it is available. Zoom in as close as you can. Compare the writing style for other words that you are sure of. This might be able to decipher the original more accurately. Ask someone else what they think it says. A fresh pair of eyes can help.

But it might just be a case of gathering supporting evidence. Finding documents with the same name and address within the same timeframe will enable you to be more confident that, on the balance of probability, this is an error. But although errors are fairly common, we should still always be open to the unexpected. People did suddenly move away for all sorts of reasons – so what you originally took to be an error might occasionally open up a whole new area of the family story, that you were unaware of because you were looking in the wrong part of the country! Genealogy is detective work. It’s all about spotting the clues.

Activity 4: Handwriting & Literacy

Scroll through the slides. Read the documents and answer the questions.

Birth, Marriage & Death Certificates

Much of the evidence to build your family history comes from certificates generated by major life events such as birth, marriage and death. These are all kept on national registers. You can access the basic entry for free on the Free BMD website, and via the major genealogy websites. These give you the basic information but if you want to get the full details you will need to see a copy of the original certificate. Some of the genealogy sites offer scanned copies of certificates and registers on either a subscription or pay-per-view basis. Or you can obtain copies from the General Register Office but these will cost you from £8 per copy. This soon mounts up so it is well worth asking other members of your family if they have copies in their personal records. They might be able to send you a photograph or scanned copy for free. As you go back a few generations, you will also find that you are not in touch with all of the people descended from your ancestors. If they are also researching their family history they might have uploaded certificates onto one of the genealogy websites. It might be possible for you to share certificates and maybe even share your research on that particular branch of the family.

Birth Certificate

Now let’s look at the different information you can glean from the birth certificate.

Marriage Certificate

Marriage certificates can also reveal a wealth of useful information.

Death Certificate

Death certificates also given an indication of how your ancestor lived in the final days of their life.

Activity 5: Birth, Marriage & Death Certificates

Choose a family member who you have an address and birthdate for.

Go to Free BMD and try to locate their birth, death or marriage certificates in the registers.

Resources

- Free BMD: https://www.freebmd.org.uk/

- General Register Office: https://www.gro.gov.uk/gro/content/

Using The Census

The purpose of the census is to gather information on the population, providing the information that the government needed to develop policies, plan and run public services, and allocate funding. It recorded all the people in any given residence or home on the specific night of the census. It describes who is in the residence, ages, relation to the head of the household, occupation or profession and where they were born. If people were staying somewhere else on the night of the census then they would be recorded at the address they were visiting. This was considered the most effective way to ensure that everyone was counted once and only once. The enumerator would collect details of everyone who slept in that dwelling on census night, which was always a Sunday. The collected forms were copied into enumeration books. Given that many people could not read or write and needed help to complete the forms this provides at least two opportunities for transcription errors. Now that the censuses are being transcribed prior to being stored online, this adds a third.

The UK started recording a 10-yearly census in 1801 although for the first four (1801, 1811, 1821 & 1831) the returns only listed the head of the household, so most individuals were excluded. They were also not collected centrally and as a result many have been lost. This makes the 1841 census the first to be widely accessible and of general use to genealogists. For reasons of confidentiality census documents are not released to the public until 100 years after they were conducted. No census was taken in 1941 because of the Second World War and the 1931 census for England and Wales was destroyed by fire in 1942. This means we will not see any meaningful update to the census information we currently have access to until 2051.

Click through the slides below to find out how the census changed over time.

As you can see, census data can provide a really useful insight into family life. It can also offer supporting or supplementary information to enable you to identify other members of the family and the communities they lived in.

You can access free census transcripts through FreeCEN.org.uk and scanned copies through various commercial genealogy sites, for which they will charge, either a subscription or pay-per-view option. You can also view them at the National Archives in Kew or Aberystwyth. There will likely be microfilm or microfiche copies at local and county record offices. Libraries also sometimes offer access to commercial genealogy websites.

Activity 6: Using The Census

Choose one of the people you have identified from Birth, Marriage or Death Certificates and see if you can find them in the Census. Look out for what further information this might give you on family, employment and community.

Resources:

- FreeCen.org.uk provide transcripts of all census returns up to 1911.

Other Useful Records

Although the census, birth, death and marriage certificates might be the most common documents we turn to, there are many more. Remember, good research is about rigorously testing your findings, so the more documentation you have, the more certain you can be. With so much documentation now being available online, it is easier than ever to find these documents but don’t forget to check with family members and explore forgotten shelves and shoe boxes to see what else you might find. Some families save their certificates scrupulously, others less so, but if you are lucky you can find all sorts of information. Here are just a few examples of other documents you might look for.

Activity 7: Other Useful Records

Look again at the ancestors you have been compiling records for. Think what other documents might be available. Were they old enough, wealthy enough or male enough to feature on the Electoral Roll? Were they of the right age to be conscripted during the Great War? Make notes of what you might want to investigate further.

Resources

- The National Archives: Family History: A collection of links and guides to help you find information both in the National Archive and elsewhere.

The Unexpected

In genealogy we should learn to expect the unexpected. Families often faced challenges which significantly impacted on their lives. Some they might have had to keep secret as a result of the harsh and judgmental attitudes of society at the time. If we are interviewing people who are still living, we should remember that such circumstances may well have been stressful and traumatic and bring back painful memories. Tact and discretion need to be applied.

Activity 8: The Unexpected

Choose one of the issues listed above that you are interested in researching in more detail. This time we will try using a search engine. Define your search as clearly as you can, for example Poverty 1800s UK. If you want to narrow it down further your might want to add rural or urban – or perhaps the name of the village, town or county your ancestor lived in. Try using search tools to focus your search and exclude unrelated suggestions.

Resources

Discovering Context

Sometimes we know what happened to our ancestors – but we struggle to understand why it happened. Understanding what else was happening in the world at that time can be a great help. Social History enables family historians who want to go beyond basic lineage to discover how their ancestors actually lived. Our ancestors’ place of birth, residence, employment, class, ethnicity, gender and whether or not they had a disability, all impacted on how they lived their lives. While histories focusing on such aspects of life are unlikely to refer to our ancestors directly, they may well refer to the streets, communities and types of work etc.

For example the 19th Century saw a huge movement of people from the countryside to the towns and cities. The Corn Laws kept wheat prices high while the spread of farm machinery reduced employment opportunities. In 1830 an agricultural worker’s average income was 9s a week while average outgoings were 13s 9d. Enclosure had removed the chance to produce food on smallholdings and many families faced starvation. Migrating to the city offered a better chance of work and higher wages than the countryside. Between 1815 and 1880 the population of London trebled to 3,188,485. But the cities were overcrowded and unhealthy. Several families would be packed into crowded and damp tenements with little sanitation. Public health suffered. In the political debate that followed numerous reports recorded the lives of people in both rural and urban environments. Many of these are held either online or in local museums and can provide a rich understanding of what life was like at the time.

In the webinar below Dr Michala Hulme delivers a webinar discussing how you can turn an entry on a document into a broader understanding of how our ancestors lived. The webinar was produced by FindMyPast and search examples inevitably focus on their site but the information here is widely transferable.

There are many sources of contextualising information you can use in your research. Local museums, libraries and local history societies hold a wide range of information specific to their local area so it is well worth contacting them. Most of them also have an online presence so even if you are researching places that are not local to you, you can probably still begin to find out something. Historical studies by social historians such as Asa Briggs, A.L. Morton or E.P. Thompson can provide rich context. So to can studies and reports that were written at the time and have subsequently been published as books or online. Sometimes it can be worth just typing a name or address straight into a search engine. It can turn up something that you might have been completely unaware of, such as improvement orders or court proceedings.

Activity 9: Discovering Context

Choose one of the ancestors that you have been able to identify in the census. Try and find out more about either their local neighbourhood or type of employment. Maybe you can find maps of the time or reports of the local economy or industry.

Resources

There are lots of books that might be useful to contextualise our ancestors lives. Here are a few examples that you should be able to get from your local library.

Primary Texts

- Rural Rides by William Cobbett: During the early 1800s Cobbett undertook a series of rides through southern England in order to report the lives of the people he met there.

- London Labour And The London Poor by Henry Mayhew: The co-founder of the satirical magazine Punch explores London in the 1850s, providing rich detail of working class lives, tastes, humour and opinions.

- The Condition Of The Working-Class In England In 1844 by Friedrich Engels: Informed by his knowledge of the Manchester textile mills, Engels explores the lives of the working class during the industrial revolution.

Secondary Texts

- A Social History Of England by Asa Briggs: A study of English society from prehistory to the present day, using literature, art and politics in an attempt to gain an understanding of human experience.

- A People’s History Of England by A.L Morton: A complete social and political history of England, from the first prehistoric settlers to the Great War.

- The Making Of The English Working Class by E.P. Thompson: This account of working-class society from 1780 to 1832 revolutionized our understanding of English social history.

Websites

- British History Online: A vast collection of primary and secondary content relating to British and Irish history,

- Old Maps Online: Find historical maps by location. See the streets your ancestors lived on and how their neighbourhood evolved.

- JSTOR: A digital library of academic journals, books, and primary sources, including a large history section. A free account option is available.

DNA Genealogy

There is a lot of publicity around the use of DNA to trace our ancestry. A whole industry has developed around this – but its proper use is controversial.

DNA stands for deoxyribonucleic acid and is passed from parents to their offspring, carrying all the information that a living organism needs to grow and function. Ultimately, all of humanity is related. Although the population has increased significantly as we move forward through time, our number of ancestors increases as we go back in time. The further back we go, the smaller population and the more overlap between ancestors. This phenomenon, known as ancestry collapse, means that we come to a point in time, not so long ago, where we all have common ancestry. Mathematically the whole population of England would be related to each other by around thirteen generations (about 1200 AD). Going back still further, using DNA evidence scientists can trace all of humanity back to Africa. All humans share about 99% of their DNA but over time small mutations to the DNA can be used to identify similarities and differences between individuals and populations. It is very important to note that DNA testing does not support a biological basis for race or assumptions based on race. Scientists still consider race and racism to be socio-political constructs. If you want to find out about this in more detail please click here for an article by Professor Alan Goodman.

The science of genomics is a developing area and the ethical implications of it are still developing, most notably what use your DNA can be put to once you have submitted it and the implications it has for people who you may not even know you are related to. Like any company that holds databases of customer information, DNA companies have been subject to data breaches. Be aware of what information you are submitting and what the implications are. The commercial use of DNA by genealogical websites uses a simplified version of the science which largely relies on crowdsourced comparisons, so it is possible for results to fluctuate depending on the population they survey. There are different types of DNA and different types of DNA test. Which test you choose will depend on the family relationship you are investigating. Different companies offer different tests so you should be clear about what your testing goals are before you got to the expense of testing

DNA is another source of information that can potentially identify a familial relationship although it can often be hard to pinpoint the exact nature of that relationship without further evidence. If you are going to use DNA testing it should be undertaken in parallel with traditional genealogical research. Also we need to remember that biological relationships are not the only familial relationships and we should be wary of focusing on DNA testing to the extent that we lose track of the very real and important relationships formed with step-family, extended family and friends.

What DNA Ancestry Tests Can And Can’t Tell You is a short video from Vox, summarising the main points of the debate, looking at its accuracy and some of the political and ethical issues that arise.

If you would like to learn more about DNA genealogy we strongly recommend you take a course in the subject before committing to any expense. There is a good course from the University of Strathclyde, available through Futurelearn that we have included in the resources.

Resources

- Genetic Genealogy: Researching Your Family Tree Using DNA: If you want to learn more about the use of DNA testing in genealogy, this course from the University of Strathclyde, looks at it in more detail. It is available on Futurelearn, which offers short-term free access options as well as paid subscription options.

- Race Is Real, But It’s Not Genetic by Professor Alan Goodman: In this essay Professor Goodman provides a detailed explanation of how there is no genetic basis for the separation of races. Instead he points to socio-political construction and consequences.

Online Resources

Over the past few years, a wealth of genealogical resources and tools have been made available online. Many different archives and indexes have been put online, many allowing you to actually see copies of the records you are looking for. There is also a vast range of family history sites and family tree builders that enable you to quickly see your family tree grow before your eyes. This can make our task much easier as we can conduct much more of our research in spare moments rather than having to find the time to journey everywhere in person. We have included a list of useful sites below – but there are also a few problems you should be aware of when using online tools.

Okay, keeping all that in mind, let’s look at the websites.

If you prefer you can download a version from the resources.

Resources

Getting Stuck

All genealogists get stuck sometimes. Certain ancestors can prove stubbornly elusive – but we knew we were signing up to a bit of detective work before we got started! We shouldn’t let it get us down. There are a number of tips and tricks that can help you to get moving again.

Re-read your sources: You might have learned more since you last read them – and people or places that previously seemed insignificant might now take on a new importance. Was the lodger actually another family member or close friend?

People lie and mistakes are made: Even on official documents people might not tell the truth: About their age; were they old enough to marry, did they want to be seen as younger – or did they even know their correct age? About their relationships; was a child really a child of that person – or perhaps a grandchild (covering for illegitimacy)? About their place of birth; did someone move away from something they wanted to leave behind? Or anything else where telling the truth might have caused them problems in what were quite judgmental times.

It was common for adults to be unable to read or write: Spellings changed or were misheard, changing the information quite significantly. Look for variations of spelling and think about similar sounding names. Always look for supporting evidence.

Trace other family members: Many of our ancestors lived in extended families and close communities. By tracing them you might be able to fill in the gaps in your ancestors’ lives. Look at who was living nearby. Look for in-laws and other repeating surnames.

Check criminal, workhouse and military records: If someone has a gap in their timeline it might be that they were in an institution such as the workhouse, prison or military. There will be records of this somewhere – but if you don’t know it might not occur to you to look. Criminal records will record the trial and offence. Workhouse records will often have an address or contact details. Military records will record next of kin and home address.

Walk the same streets: If you can arrange to visit the area, this could reveal a lot of new information. But it could be time consuming or expensive to get there – so plan your trip first. What do you know and what do you need to know. What local resources are available, what are the opening times and do you need an appointment? If this is not practical, try to find maps of the period. Seeing how a community was laid out can help to improve your understanding.

Should you re-interview your relatives? If you interviewed a relative early in your research you might need to follow this up as you learn more. If you didn’t know about something you couldn’t ask them about it. Your relatives might hold the key. They may have assumed you knew something that you didn’t.

Understand context: It might help to understand why your ancestors did whatever they did. What were the important historical events or trends that might have impacted on their lives? How might this have influenced their actions? This might give you a clue where to look for further evidence.

Search newspapers of the time: Local newspapers often reported events that involved local people and often gave both name and address, especially in court reports. Newspaper archives are searchable by name, date, location, keywords etc.

Reword or refocus your search: Try variations of your ancestors name and different spellings. If you have been looking for a name, try looking for an address or an employer. Try searching for other family members.

Come off genealogy sites and try searching more widely: Using general search engines may be a bit random but it does sometimes yield results, turning up something we were completely unaware of. Once again, try different search terms that might relate to your ancestor.

Write it down: Writing out the key points of your ancestors life as a short story engages your brain in a different way to checking forms and lists. This might help you to identify missing bits of information or links to other records.

Review, review, review! Remember our research diagram earlier. Every new piece of information is another piece in the jigsaw. Remember to take a step back to look at how this affects the bigger picture. Keep reviewing the information and look at how it fits together. It might be different to how you first thought. Keep going through the process and, slowly but surely, the gaps will become fewer.

Activity 10: Getting Stuck

Return to an ancestor you have researched previously. Using the tips above, see if you can find out anything new about them.

Pulling It All Together

Once you’ve discovered all this information what do you do with it? We’ve already discussed the importance of saving your information somewhere safe rather than just on a website. We’ve also discussed the various files and charts that you can download and fill in. Other versions are available in book and folder options and are available from stationers and book shops. You could also think about pulling your research together in a book, album or interactive timeline. This could enable you to present a mixture of scanned documents, photos, charts and explanatory text. These days the options are endless.

The first step is to download all the documents you have found online. Save them together with the physical documents and photos you have found. You may want to scan those into your computer as well. You will need to index these documents or have a filing system that makes them easy to find. Using a computer means it is really easy to cross-reference between different family members. But of course you can keep them as hard copies in a physical archive as well if you wish. At the very least you should keep your documents and research stored to an external hard drive as a back up in case your laptop crashes.

How you present your research will depend on who you want to share it with. A book or album is a great way of sharing your family history over time. Once printed it will be there forever and it could become a treasured family heirloom. You can print as many copies as you like – but it will probably be a very limited run so can be quite expensive. Most commercial genealogy websites offer options to print albums through commercial partners. These are easy to set up but with limited design options, but if the design works for you then they could be a good option.

Of course, it is unlikely that your research will ever truly be finished. There will always be new things to look into and discover – so perhaps you need a format that is more flexible, like a collection of loose leaf folders you can add to and rearrange as required. Or an e-book that you can keep working on and expanding as your research progresses. You can design something yourself in Word or with desktop publishing software. These can then be saved as pdf file either as a e-books or printed if and when you need to. If you need to improve your desktop publishing skills there are courses available on this website, such as for Scribus the open source desktop publishing software.

You can also print off artistically designed family trees to hang on the wall. Once again the commercial sites have options for this but as we saw in the family tree section you can also find free templates online. Or why not design your own?

The options are as many and varied as our families are. Investigate the different options and see what works for you. Good luck – and have fun!

Activity 11: Pulling It All Together

Think about how you would like to present your research. What most clearly explores your ancestors lives? What presents your information most clearly? What is easiest to share? What is most practical and cost effective for you? Which is the most flexible to allow you to expand as the results of your research grow?

Course Completion

Thank you for participating in this course, we hope you found it interesting. Hopefully you have gained a broad understanding of genealogy and how to go about discovering your family history. If your research leads you to make interesting discoveries that you want to share please contact us and we will share your story on the website.

Feedback

Your views are very important to us, please click on the link below to let us know what you thought of this course.